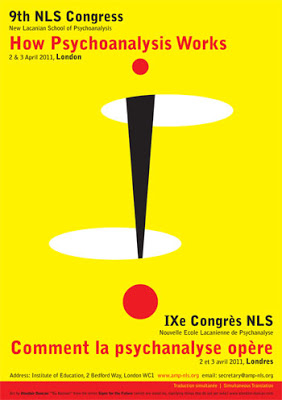

| 9th NLS Congress London, 2/3 April 2011 How Psychoanalysis Works |

||||||||||||||||||

| Argument

« How Psychoanalysis Works ». This is not a question, this is an assertion. Because psychoanalysis indeed works, contrary to what some noisily object to nowadays. Still, we need to account for it. The word ‘work’ (opèrer), used in an intransitive way, is a strong word. Coming from the Latin ‘operari’, which means ‘to work’, ‘to operate’ or ‘operation’, it involves an action that produces an effect, an « ordered sequence of acts that effect a transformation » (according to ‘Le Robert’). To say it in a matter of fact way: psychoanalysis changes something, it yields results. By what means and with what aim is what we will show. At the end of his teaching, Lacan said that for all these years he did not stop questioning his ‘co-practitioners’ « on the subject of knowing how they could possibly operate with words – I don’t saycure, one does not cure everybody. There are operations that are effective and that only happen with words. »[1] The power of the word was also what Freud, inventor of psychoanalysis, patiently gave account of to the supposed ‘impartial person’ who did not know anything of the ‘peculiarities of an analytic treatment’, whom he addressed in 1926 on Lay Analysis. The specific use of words in the meeting of a psychoanalyst with his patient is neither suggestion nor magic. The way words are used cannot be captured by other practices or any previous knowledge. Freud says: « analysis is a procedure sui generis, something novel and special, which can only be understood with the help of new insights – or hypotheses, if that sounds better. »[2] Freud considered that the hypothesis of the unconscious and the importance of sexuality in the determination of neurosis were the two ‘cornerstones’ of psychoanalytic theory, deduced from the experience.[3] To give our own account of how psychoanalysis works today, let us start from what our daily practice teaches us. Let us not hesitate to take things from the level of the phenomena. Let us ask ourselves what in a given case took place and what was at work. By doing this we will prove that this ‘how’ neither goes back to, nor culminates in a practical guide that prescribes procedures to follow for foreseeable and generalisable results. We verify again, as at the Congress of the WAP in 2004, that Lacanian practice is without standards, but that it is for all that not without principles. In order to orient ourselves, let us return to the ‘fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis’, as Lacan chose them from Freud in 1964, to revive them. Seminar XI is a very particular moment in his teaching, a rupture and a new departure, the stakes of which have often been illuminated by Jacques-Alain Miller. Lacan puts a series of four concepts in order: the unconscious, repetition, transference and the drive, with which he responds to the question of what founds psychoanalysis as ‘praxis’ [4], by speaking to an extended audience beyond the psychoanalysts who followed his teaching at that point. For the unconscious to speak it needs someone who listens to it, said Jacques-Alain Miller in London, at the ‘Rally of the Impossible Professions’. A psychoanalyst distances himself from the dominant contemporary ideologies who do not believe in the unconscious.[5]He is interested in the things that are wrong, that fail, that defy mastery, and of which Lacan made the manifestation of the truth of a subject. This unconscious that ‘opens and closes’, that presents itself as hindrance and failure, how is it gotten hold of? How do we offer the possibility of surprise by proposing this special mode of speaking that is free association? What is our responsibility in an interpretation? |

||||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||||

|